A look at the nation’s first privately-owned and managed nature reserve.

By Aiden Jewelle Gonzales

“Make sure to bring a pair of water shoes,” is the intriguing direction I was given as I prepared to step into adventure at OurLand Thailand, the nation’s first privately-owned and managed nature reserve. Co-founded by Vijo Varghese and his best friend and business partner, Anshuman ‘Anshu’ Tripathy, the conservation project had already piqued my interest just based on the passion with which Vijo had spoken about it on the phone. “Mere words can’t do it justice. I’d love for you to experience OurLand first-hand and really connect with what we’re doing here,” he entreated. Despite being a self-confessed city slicker who hadn’t experienced Thailand’s wilder side in years – Bangkok’s savage traffic notwithstanding – I found myself packing my water shoes and trading the concrete jungle for the real thing three hours’ drive away in Kanchanaburi.

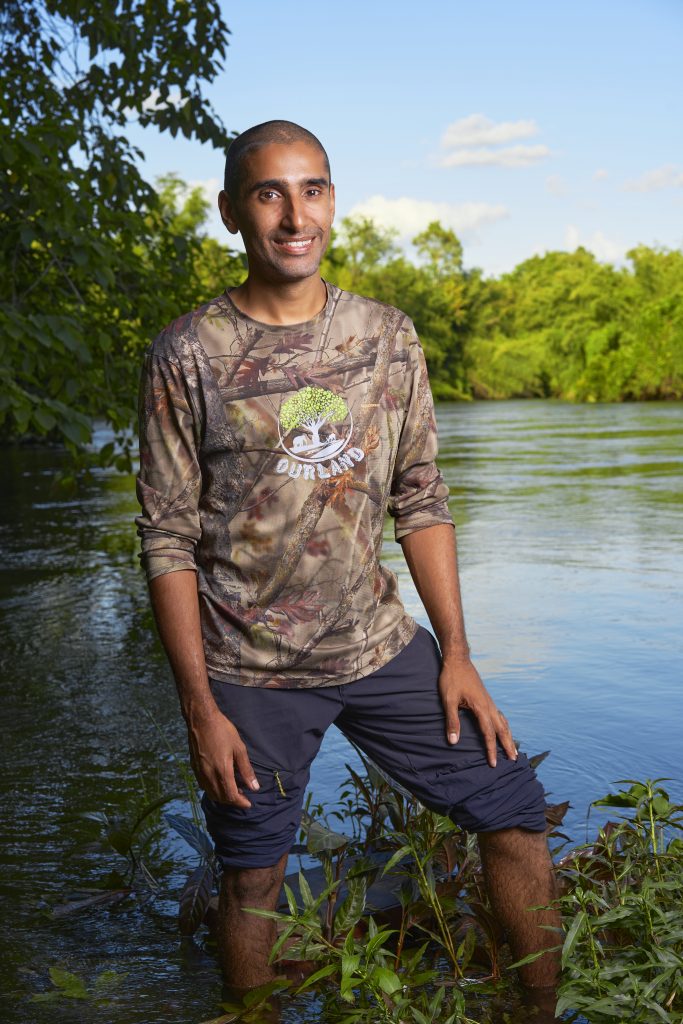

When Vijo greets us, he’s exactly what I expected: sincere, utterly at home in his environment, and with the self-possession of someone who knows exactly what they want out of life. The latter is one of the conversations that stood out to me the most throughout the day – when asked what he’s most grateful for, he answered without hesitation, “Discovering my calling. It feels good to have taken the time to explore what I like, and then take that leap of faith.”

However, the journey there took some time. Born in Muthalakodam in Kerala, India, Vijo moved to Thailand when he was six and like many kids born to Indian parents, pursued an education in a bankable degree: computer engineering. Soon afterwards, he started a career in the automotive industry, working as a junior automotive editor and then moving to Chevrolet Thailand for four years, after a brief stint with the Times of India Kochi. “I’ve always been a person who’s very driven by passion, which is why I ended up in the automotive industry. I like cars, and at the time I thought it was my dream job,” Vijo reveals. “But somewhere along the way I lost my passion and burned out. Working for a company selling cars, I wasn’t making the world a better place. It didn’t appeal to me anymore.

“What did appeal was nature – every weekend I’d get out of the corporate sector and heal myself in nature. It’s not that I hate the city. I love Bangkok and five or six years ago, I was the go-to guide when anyone was visiting. But I felt myself drifting away from that life – despite my nice apartment and my fat paycheque, my depression and anxiety worsened. Every Monday I’d wake up and hold back my tears as I listened to the city traffic going by, and I’d ask myself, is this what I really want to do with my life?”

Happily, Vijo found the light at the end of the proverbial tunnel. Shaking himself out of the sobering reminiscence, he tells us with a smile, “Three months after I moved to OurLand after I left my job at Chevy, I realized that I was still happy to be here. That’s when I knew this was what I wanted to do.” And what is it exactly that he does here? We settle down around him like children agog for stories of great exploits, equally curious and fascinated. And, like a modern-day Bilbo Baggins, Vijo begins his tale.

“30-40 years ago, the Thai government gave away the land by the Khwae Yai River here to farmers,” he explains with a map of the area. “Somewhere along the way, a real estate company bought chunks of the land, but they went bankrupt during the Tom Yum Kung Financial Crisis in 1997 so they weren’t actively maintaining it. Meanwhile, on the other side of the road is Thailand’s first government-owned wildlife sanctuary, Salakpra Wildlife Sanctuary, which is home to a variety of animals – from elephants, to deer, to big cats. The issue is that the animals need access to the river to drink but to do so, they have to cross private land and they either get shot at, electrocuted by electric fences set up by the farmers, or scared away by firecrackers. They’ve since realized that the only safe passage is through the unused corridor owned by this real estate company, and that’s why we’re located here. We’re leasing 26 rai and have helped to reforest the area, and our aim is to expand further so we can get a larger safe passage for the animals.”

When asked what sparked this idea, he shared OurLand’s very humble roots: “Originally, it was a simple ‘return to nature.’ I had taken a trip to Nepal and I’d met a man there, Moti, who’d only had a third-grade education, but owned a guest house and was far happier than I was in my high-paying career, and that made me re-evaluate things. During one of my weekly trips out of Bangkok, I asked the owners of the elephant sanctuary that I was volunteering in if they knew a place that Anshu and I could lease, and when we visited the area, we saw elephant and deer footprints, which convinced me that this was where I wanted to be.”

Indeed, walking in the literal footsteps of these animals is symbolic of OurLand’s core concept; one where humans and wildlife can live together in peace, sustainably. “It’s not just their land or the humans’ land,” Vijo says, impassionedly. “It’s our land, together. We don’t own any of the animals – they just come and go. It’s our business to ensure that the environment is pristine enough for them. To that end, we’ve also set up an eco-village which is completely off grid; it’s run on solar power and we build our own shelters so people can experience life in the middle of the jungle, disconnected from the rest of the world. It’s also become an educational centre for people to learn about the ecosystem here and the importance of sustainability, and to help children get rid of their bio-phobia. The latter will probably be the leading cause of habitat loss worldwide in the near future.”

True to form, Vijo continues to educate us as he leads us to the conservation project’s newest venture, their organic farm which is set up across the river from the eco-village. “The primary pillars of sustainability are food, water, shelter, and energy. We can produce three of them inside OurLand: energy, water, and shelter. But every time we try to produce food, the elephants come and eat it! So we set up the organic farm.”

The greenhouse we’re brought to is deceptively large, and as I make my way through neat rows of dirt, I’m impressed by the range of produce housed there, from cucumbers, to cantaloupe, pumpkins, and tomatoes. Even here, sustainability reigns supreme. “Base one is producing enough food to feed yourselves, so we have food for us that live at the eco-village and for our visitors,” Vijo says. “Then with our surplus, we give the food to the local community for free. It creates a bond, and they’re more likely to collaborate with you in the future because they know you have their best interests at heart. From there, you process the food into a form that you can keep for later, and only after do we sell it.”

This non-profit system stood out to me, and I ask him how he monetises the reserve as it can’t be very lucrative on its own. “Although we are officially registered as a for-profit company, we operate like an NGO,” Vijo acknowledges. “We generate revenue by people coming to OurLand to take a trip out in nature, or children whose schools or parents want to educate them about the environment. We also get donated money as well. It helps that we generate our own electricity, water, and even our shelters are made from the dirt under your feet.” He explains, however, that it wasn’t all a walk in the park – or in the jungle, as it were. “In the first two years, Anshu and I put in a lot of personal money. It was hard when we didn’t have guests, and we had to work to get things rolling. The COVID-19 pandemic was another thing that really tested us. 95 percent of our guests are from abroad, and we had no local guests either, so we completely shut down for a few months. But in a way it was a blessing in disguise – we had to re-evaluate how to become more sustainable, and that’s when we set up this farm.”

Having gotten our feet wet, as it were, it was time to dive into the thick of things, and here I realised why the water shoes were necessary. Donning life jackets in a non-traditional manner, we streamed into the Khwae Yai River one by one so that we could float into OurLand itself; a suitably memorably introduction to the reserve. As I drift along the river, spotting monitor lizards and birds with distinctive plumage along the way, the current allows both our worries and self-consciousness to float away, allowing for words to flow as freely as the water around us. “This is possibly the most fun part of the trip,” Vijo allows, “I’ve done this maybe 400 times but I never get tired of it. I love about 90 percent of all the things I do, but the aspect that I love the most is probably the freedom of being in nature, and interacting with animals, from the elephants and deer that visit, to the snakes I’m called to catch.”

Despite his clear passion for every aspect of the project, the choice of career path is unusual, especially from someone within the Indian community, and I ask him about that. “I haven’t been asked this by any publication before,” he says with a laugh, “so I’m going to go full blast on this one! First of all, my dad was very troubled by my lack of discipline towards going the traditional route of using my computer engineering degree to get a computer analyst job.

“When I jumped into this, they didn’t have as much of a say but they are to this day upset that I go out and catch snakes for a living. When I was in Kerala, catching snakes is considered a very lowly profession, and that’s something that I do quite often, so that’s always something that my mum finds hard to accept. It has been tough for sure, but their mind set has changed over the years, although I doubt they fully grasp the intensity of the project itself.

“As for comments made by other relatives and the community – I guess out of sight is out of mind. Some of my relatives think I’m a lunatic!” Vijo chuckles. “I’m here in Thailand, so I have that distance.” He stops to quote Our Deepest Fear by Marianne Wilson, a poem that he says has helped him cope with the naysayers. “Our deepest fear is not that we are inadequate. Our deepest fear is that we are powerful beyond measure,” is perhaps the most famous line of the poem, and it’s clear that it brings Vijo comfort during tough times. Nevertheless, Vijo tells us that he has no regrets except perhaps not finding his calling earlier. “Making a decision like leaving Bangkok and then living out here in the jungle, I think that’s caused a lot of pain to some people in my life and I wish that was not the case.”

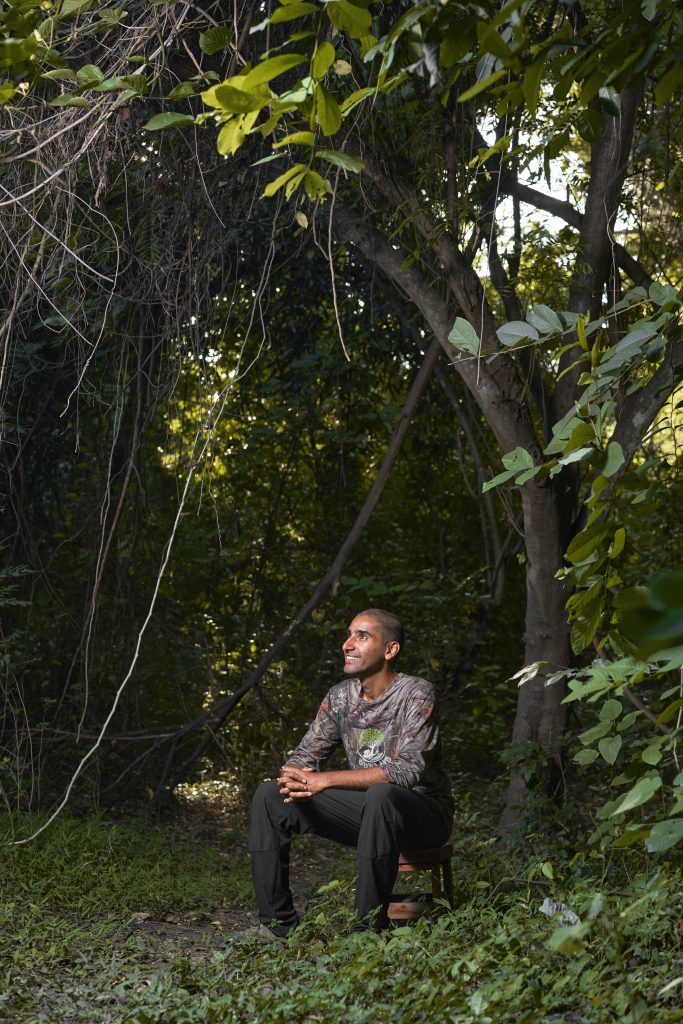

Arriving at the other side of the river half an hour later, I feel like the trip both down the river and memory lane has enabled me to better understand the driving force behind Vijo’s passion. As we shake ourselves off, Vijo strikes out towards the jungle, eager to educate us about the ecosystem that OurLand strives to protect. As we walk past lush greenery and century-old trees, Vijo makes sure to point out areas that have been ravaged by humans and are only now starting to recover. On the way, he tells us about the activities that OurLand promotes to help nature conservation – from the river float that we’d just experienced, to their Community Tree Planting, to their courses on banteng conservation, human-elephant conflict, bats and caves in Kanchanaburi, snake education, and sustainability education.

As we follow the elephant trails, I ask how the local community is involved and how this education has helped them over the years. “At a very basic level, we include them through tourism. The guests that come to us from abroad are taken to the local communities so that they can generate revenue from them. The locals also learn about ways to more humanely prevent wildlife from destroying their crops – instead of electric fencing, they now use honeycomb fences and the bees deter the wildlife, while providing them with honey that they can sell. In a way, it’s symbiotic.” As he speaks, it’s clear that Vijo’s love for nature extends to the local community that lives in it as well. “We only hire local staff, and we train them all, which is another form of income for them.”

Upon reaching the eco-village, Vijo walks us through how they incorporate technology into their off-grid lifestyle. “Firstly, we use solar cells to produce electricity, and secondly, all the water management systems are computer-controlled. I’m a fan of embedding technology into things. We even have a timer-controlled organic farm watering system.” However, a lot of the village is still very grounded, literally. The bricks used to create shelters, for example, are created from mud that they’ve dug up in the forest and sun dried. “This is going to be my new home,” Vijo tells us with pride as he showcases a structure he built himself, be it ever so humble. Walking a few hundred meters down, he points out the thatch hut that he’s been living in for a few years now, with just enough space for a mosquito net and bedding. “It’s definitely a step up!” he says with a laugh.

When asked whether he misses the creature comforts of home or whether he feels isolated here, he answers, “I’m a massive extrovert, I love connecting with people, but in recent months I’ve really enjoyed having time for myself, just being alone. It helps with planning what OurLand should do moving forward. I’ve realised I don’t always have to jump into things. We should take time to reflect on what we really need to do.” As I stand there, away from the frenetic whirlwind that is Bangkok, I realise that is one of the biggest gifts of the place – a time to connect with the soul of nature and thus, connect with who we are without the distractions of life.

For more information about OurLand, visit their Facebook: @ourlandthailand

www.ourlandthailand.com