Originally from Punjab, my family moved to Thailand in pursuit of new opportunities, and as a result of the partition in the 1940s that forced millions to migrate to different countries in Southeast Asia. They travelled by land and sea, before settling in Chiang Mai, where there was a growing Indian community. It was only in the early 1950s, after years of working for other people, that my family established their own fabric business called O.K. Store.

Growing up as a Hindu-Punjabi child in Thailand I was exposed to a big mix of cultures. I attended a Thai public school, and as a result, I speak Thai as my mother tongue. Beyond school, most of my childhood memories take place in the fabric store. We lived upstairs because it was a shophouse, and after-school, weekends and school holidays were spent cutting and measuring fabric. I enjoyed spending time with my family, but I didn’t want to hold a measuring tape forever, I wanted to hold a paint brush.

When did you realise you wanted to pursue art?

As a child I was more than happy to sit down for five hours or more to draw. As I got older I realised I wanted to study art, which wasn’t considered normal at my school or within the Indian community. My parents could see I was very creative, but even then, the idea of becoming an artist worried them because they didn’t know how I would make a living.

After some convincing, I talked them into letting me attend art school and by then there was one in Chiang Mai so I didn’t have to move far away. After I graduated from art school, my mother passed away so she didn’t get to see the artist I became. However, I knew I had her support. She was confident I would make it one day.

What did you do after art school?

I received a scholarship to move to Japan to exhibit my work and I ended up staying there for a while. I was only 25 years old and looking for a new life, when I met my wife. She was an art historian and she loved my work, so she supported me a lot when I was trying to find my footing. With her help, more museums and galleries approached me to work with them.

What are some of your notable projects?

In 1995 I launched a project called ‘Taxi Gallery,’ where I worked with a driver to transform the inside of a cab into an art exhibition with paintings, video installations; even the driver’s uniform was part of it. It was a way of getting art to people, rather than waiting for them to come to me. This project was a gateway, because soon, international museums in Sydney, Tokyo and New York invited me to do a ‘Taxi Gallery’ in their cities. Years after, when my daughter was born in 2001, my focus shifted away from public art and my inspiration began to centre on my roots. I wondered,“what if, when my daughter grows up, she wants to know where she’s from?”I should be able to tell her my family’s story. So I travelled to India for the first time when I was in my mid-30s, which made me realise the city that myancestors came from, Gujranwala, was now part of Pakistan.

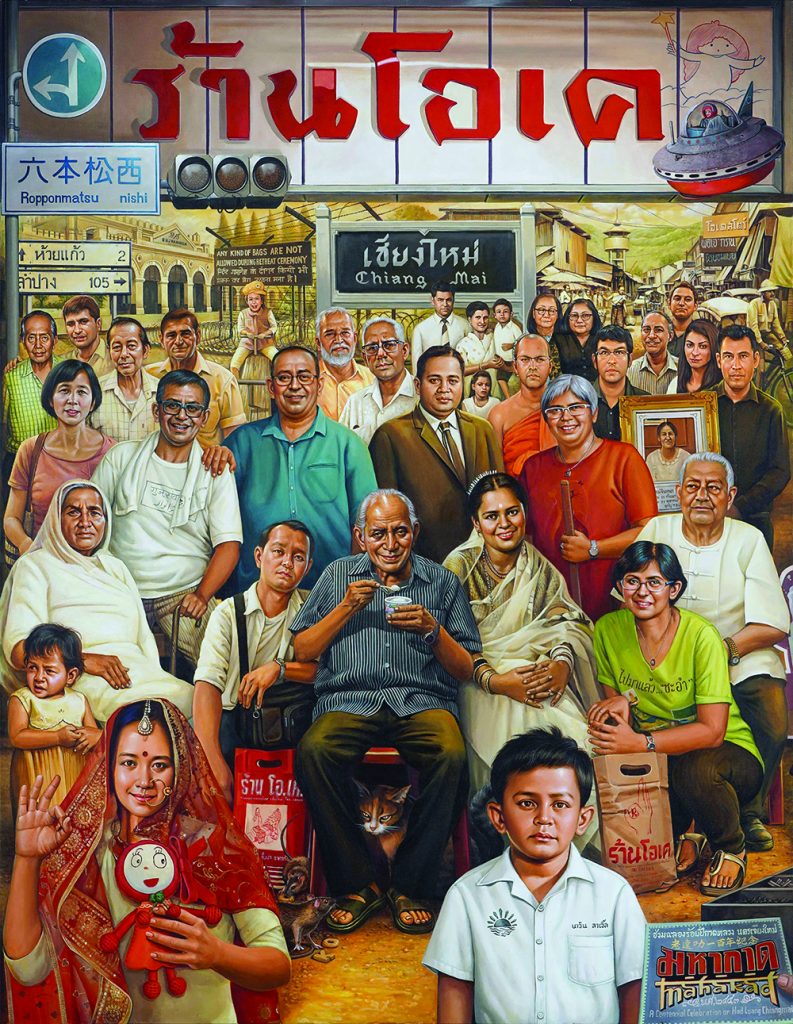

This led to plenty of research, and the development of a series of projects centred on the notion of identity. One example was ‘Places of Rebirth,’ which told the story of my family’s migration and the people they met across generations. It took the form of paintings inspired by Indian movie posters. Another example was ‘Navinland,’ where I used my name to create a ‘new territory’ that didn’t belong to any border. A sort of imaginary land that could exist anywhere in the world, that would make people question why we let borders define us.

Why do you use so many different types of media?

I’ve incorporated painting, photography, sculptures, comic-inspired illustrations, film, and much more into my varied projects. I like using different media because each one reaches a different target audience and I want to explore all the possibilities.

What’s the story behind establishing your own studio?

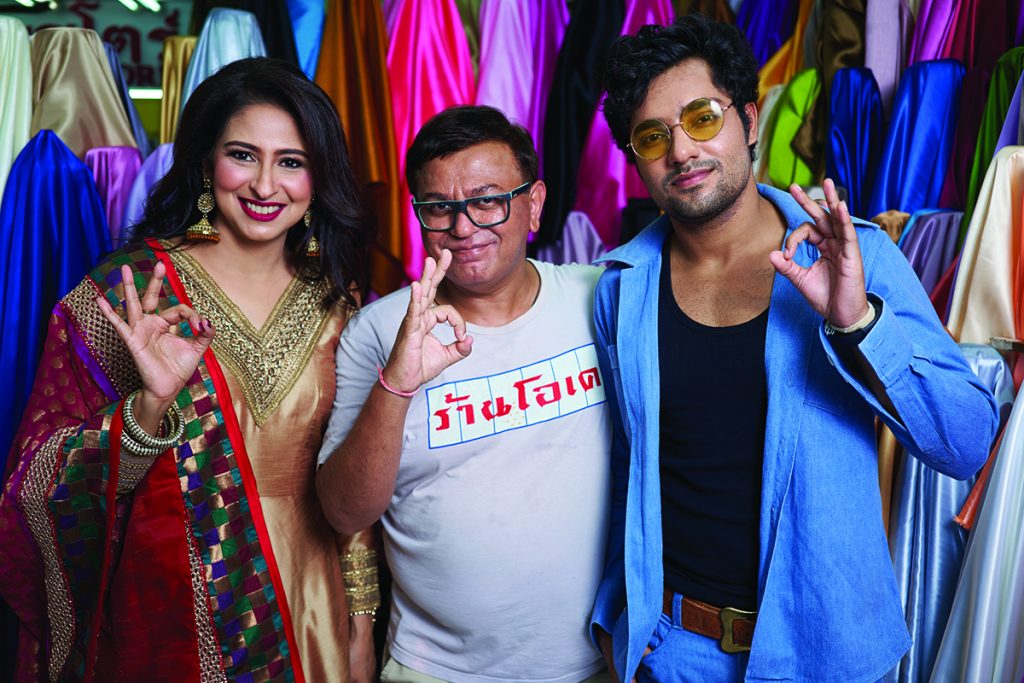

I’ve always been working under the Navin Production company and artist collective. However in 2015, to commemorate 20 years of my career, I opened a new studio called StudiOK in Chiang Mai, which took its name from my father’s fabric store, O.K Store. I kept parts of the original store, transforming it into my studio so I could house his work and my work together.

What can you tell us about your upcoming exhibition, ‘Khaek Pai Krai Ma’?

Two years ago, I began travelling around Thailand, visiting Indians in different provinces to learn about their histories. The goal was to piece together these stories and turn them into art, so the exhibition really recognises Thailand’s diverse Indian diaspora. For Indians, I want the community to come together and feel proud of our histories. For international audiences, I want people to recognise that Indians have been a part of the culture here for a long time.

The exhibition is taking place at Warehouse 30 in Charoenkrung. Years ago, the area was full of Indian workers who were part of the shipping industry, and if you walk further down the street you’re at Wat Khaek Silom. So I found myself connecting to the space, and I want visitors to feel the same. The exhibition

will feature a 30-metre long panoramic mural, a Bollywood musical-style video installation, and various talks, screenings and tours, so visitors can fully access and understand what’s being displayed.

In your opinion, what does it mean to be Thai-Indian?

If you talk to any Indian in Thailand, they’ll tell you that at some point in their lives they’ve been called a khaek, which can make you feel like an outsider. However, I think it’s time that we embrace the word khaek instead of letting it make us feel uncomfortable, because it really means we’re part of an incredibly dynamic community that has contributed and grown so much.

We’ve been here for generations now and we still visit temples, host community events, enjoy Indian food, and celebrate cultural festivals. We should be proud that our community is standing strong, and it is so important that we continue preserving our heritage, so that future generations can feel the same pride, too.

Khaek Pai Krai Ma

14th December 2019 to 19th January 2020 Warehouse 30, Charoenkrung Soi 30, Bang Rak, Bangkok, 10500

Open daily from 1pm to 7pm.

For more information: visit www.navinproduction.com or on Facebook @NavinProduction