How his Anglo-Indian heritage has influenced his narrative of eco-awareness.

By Aiden Jewelle Gonzales

“This business is not for the faint hearted,” architect Patrick Keane tells me as he walks me through an installation of the crafted furniture for Project Rattan, composed of seamless lines and comfortable wood. “Architecture is not really a job, it’s more of a way of life. The design process drives me, not the other way around – it’s the only way to be original; to be the real deal.”

I first met Patrick at the launch of Spice & Barley, a rooftop gastro lounge at Riverside Plaza that blew guests away with its high-concept design that blended together technology and traditional Thai motifs. The result was a dynamic space where towering 3D-printed columns swept the eye up to the vaulted ceilings of billowing rattan waves; cutting-edge design suffused with natural charm. Painted gold, the space channelled the serenity of Thai temples while echoing the skyscrapers of the sprawling city outside. “I designed it,” he tells me with a laugh when I expressed admiration for the striking interior, “together with my company – I’m the founder and Director of Enter Projects Asia.” When asked about what drives such a distinct point of view, he answers, “Originality and an ecological agenda. There’s always something you can do to make a difference, and I think it’s time to leave the planet in better shape than the one we are living in.”

Indeed, I soon discover that Enter Projects, which was previously based in Patrick’s home country of Australia, specialises in using technologically-aided, 3D design to create interiors and exteriors that are eco-friendly, innovative, and yet grounded in the culture of Southeast Asia and the Pacific. With a list of projects that includes well-known venues such as Vikasa Yoga, Fraser Suites Sukhumvit, and Angsana Laguna Phuket, the company’s latest ecological initiative, Project Rattan, was fostered in lockdown. “Rattan is the world’s most sustainable material,” Patrick explains, “the project’s all about working with local arts and crafts of Thailand in meaningful ways, and producing contemporary design. Many of the rattan workers have five generations of skill behind them, but their craft is being replaced by plastics. We wanted to introduce this talent into commercial settings and in doing so, we stopped two factories from closing down. We’re also continuing with brick and other local materials.”

I point out that it’s refreshing to meet an architect from outside the region who isn’t adamant about importing Western-based designs, and in response Patrick cites his international heritage and background in helping him understand the importance of grounding his designs in local culture. Born in East Africa with Australian and Anglo-Indian heritage, Patrick has lived in five continents, having grown up in Australia and England, and completed his masters in Architecture at Princeton University. “Blending international training with the global and local team is where innovation takes place,” he says. “It’s incredibly important to make sure one’s work is to an international standard but resonates deeply with the local culture. Gone are the days where people will accept imported designs or superficial ‘Thai’ elements. Now the age of Asian fusion is here, in design at all scales. For example, we are currently working with families that own brick pits in the South of Thailand, who will supply three contemporary projects for us.”

As he walks me through his different designs – from the Vikasa Yoga studio that ensconces you in warm wood and undulating lines, akin to a bird’s burrow; to Angsana Laguna Phuket’s restaurants with their immense pillars that mushroom out into a canopy above – I notice that each one creates a space that is alive and rooted in its environment. “Eco-awareness is incorporating nature into an urban context, creating architecture that is fluid and organic,” Patrick explains.

Project Rattan exhibition at River City Bangkok

“There is no path in nature that is straight, so we don’t work with straight lines. Currently, we are working on three houses using local sustainable and natural materials, and we are also looking into an eco-resort on the islands. It’s architecture that pushes boundaries, but it helps us have continued relevance. If a designer loses relevance, then they are wasting time – one has to be part of the spirit of the age!”

A winner of the Dezeen People’s Award, a London-based award that’s based on votes, which Patrick credits with giving global exposure to the artists and craftspeople of Thailand; as well as the Dezeen award for health and leisure; and having been featured on the cover of Interior Design New York, Patrick and his team have hit their stride, and have set their sights on going local and global at the same time. He sat down to talk to me about his design journey, his inspirations, and the role his Anglo-Indian heritage has played into his distinct designs:

Who or what is currently your biggest inspiration in terms of architectural design?

I tend to not look at other architect’s work as it clouds your vision and stifles originality. Having said that, there are occasionally pivotal projects that are game changers – Jean Nouvel in Doha, the UNStudio Mercedes-Benz Museum, Norman Foster for Apple, and Bill Bensley. I admire their projects and the ‘methods to their madness,’ as well as their ability to take risks. Bangkok is also an inspiration, and has some of the best buildings in the world now. To do something on the scale of King Power Mahanakhon is next on the list for us.

Spice & Barley restaurant at Riverside Plaza

How has your Anglo-Indian heritage and your family’s background in India inspired your design aesthetic and ethos?

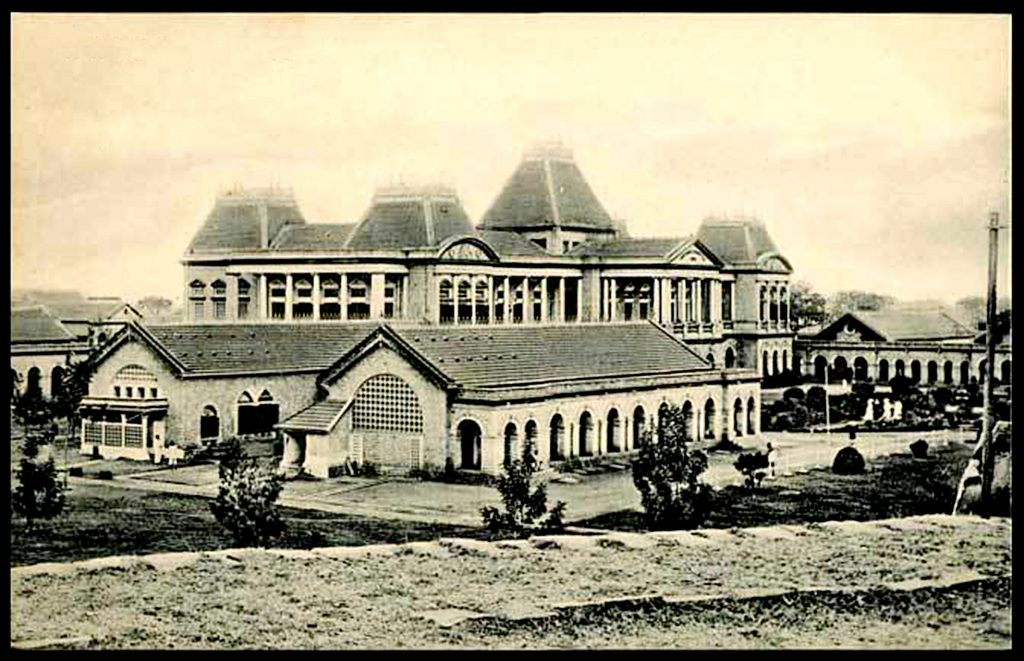

My great-grandfather married into an Indian family, and my mum was Anglo-Indian, with her whole family from Bangalore, although she was born in Dehradun. That side of my family have been in India since 1725 working in shipping, and in fact my great-great grandfather, Charles Andrew Welsh, was a prominent architect In India, designing several large public buildings, chief among them the Victoria Hospital in Bangalore.

After a great-aunt found out I was studying architecture, she wrote me a long letter explaining the story and suggested that I visit it. After my master’s, I saved up the money to go, studying the building carefully with two separate visits. Designing a space that heals people for 120 years is quite something, and it was a huge influence on my architecture, with its example of passive design through its tall ceilings, fantastic deep balconies, and cross ventilation.

India has always had a big impression on me, and in general I think Indian architecture is timeless, with its integration of gardens, natural materials, and wells. All of these things rub off on me of course, and I’m a better architect for it.

The Victoria Hospital in Bangalore, completed in 1900

What led you to Thailand?

I moved to Phuket with my wife and baby son for a large, eco master-planning project. Thailand is very diverse and a global player on the cultural scene, and I find the transformation that Bangkok’s art scene is undergoing really fascinating – for example, in River City where we have our Project Rattan, there are pockets of interest sprouting everywhere.

Although each space you’ve designed is quite distinct, what would you say is the theme that ties together all your designs?

Blending the latest technology with regional arts and crafts, and local materials. We use a lot of geometry that works on different scales, generated by us using computer scripts to simulate waves, dunes, corals and other forms in nature, and we work with the marine industry and aviation software platforms to achieve this. Then we look to alternatives in fabrication, with designs staying in-budget.

When asked to design a space, how do you approach it? How do you meet your client’s brief while still injecting your own personal style?

I try to really understand the client’s personality or the ethos of the company. We have a large repertoire at many scales, so we have something for everyone and we are not expensive. My personal style is always evolving with every project so I like to surprise clients, while keeping myself interested. The only people I cannot work for are projects that have no environmental objective. My personal preference is to work on difficult projects that challenge us both, introducing nature into the built environment. It’s not hard to convince a client that we should introduce nature into the design – they usually know they need it, they just often don’t know how to do it.

Headquarters of Vikasa Yoga; Photography by Edmund Sumner

What was your biggest architectural challenge over the years?

Sadly, the construction industry is a dinosaur and unwilling to change. The side effects are conservative design, expensive running costs due to poor material choices, stagnant work methods, and catastrophic levels of pollution. Now, we work with clients that are accepting of our input, with some big companies coming to us for ingenuity in cost-saving while going natural.

If money or pragmatic constraints were no object, what is the dream project that you’d like to design?

I’d really like to redesign the World Trade Centre in New York. I don’t think they’ve found the answer yet.

Secondly, I want to create a masterplan to reinstate the khlongs in Bangkok, and make them a primary mode of transport with electric boats, similar to Venice but in an Asian context. We could build towers that suck up the flood water, with planting that could be a way of solving the flooding problems of Bangkok. At the end of the day, architecture is meant to be innovative; a way to solve problems.

For more information email info@enterprojects.net or visit www.enterprojects.net