A deep dive into the complex world of fabric production.

By Aiden Jewelle Gonzales

When I met Kulthorn Narula, a mainstay in the fabric industry in Thailand for 52 years, he asks me in his usual soft-spoken, knowledgeable way if I knew what went into producing the fabric for the floral dress I was wearing. “After the fabric is woven, it has to be scoured and then bleached, and then there’s batching, printing, steaming, washing, drying, and finishing,” he explains. “Each machine for each of these processes costs THB 20-30 million, so you can see why the fabric industry is such a big investment.”

I admitted that I hadn’t given much thought to what went into making our clothes, or indeed how ubiquitous fabric was in our everyday lives, and Kulthorn tells me with a laugh, “even the recent resurgence of the ‘elephant pants’ trend that the whole country is wearing now is important to our industry. Factories are loaded with these prints, and we have to keep up.”

Having started working in the industry since 1972, for big names in the industry such as The Thonburi Textile Mills Ltd., Tex Master, Bangkok Printing and Dyeing, Evergreen Printing and Dyeing, and Kitpattana Printing and Dyeing; and still going strong as a Technical Consultant for V.P.C. Group at the venerable age of 74, Kulthorn Narula is someone who’s seen both the renaissance and decline of the Kingdom’s textile industry, and has appropriately been lauded for it. It’s in his lifeblood – everything he tells me shows a passion and technical knowledge for every step of the printing and processing system that is awe-inspiring. When I ask him about concerns that Thailand’s textiles industry is long past its heyday, he is adamant that there are still pathways to success, and that adaptability is key. He gives Masala his insight.

What were your personal experiences witnessing the ‘golden age’ and beyond of Thailand’s fabric industry – what were some of the highest highs, and conversely, some of the lowest lows?

After completing my education at the University of Mumbai, I started working as an Assistant Printing Manager in Thonburi Textile Mills. At that time, it was considered the first composite mill of Thailand, which means the factory had the complete span of facilities, from spinning, to weaving, printing, dyeing, and finishing; and it had just opened 6-7 years prior. The factory started with hand prints and then brought in the flatbed Automatic Printing Machine. We ran for 24 hours, with three shifts, and had so much work that sometimes we had to work on Sundays too. It was just like a start up in the textile printing and dyeing industry, and imports were restricted by heavy import duties, so whatever we produced was in heavy demand.

In 1974, due to the high productivity required, the company installed the latest invention in the textile printing industry, the Rotary Printing Machine, the first one of its kind in Thailand. It had the capacity to print 60-80 yards per minute, whereas the previous flatbed printing machine could print about 15 yards per minute. This was a huge game changer for the printing industry, and it was the golden era of the printing industry in Thailand. The demand was sky high.

Because of the high demand, we had to buy a second and third Rotary Printing Machine, and we produced up to 2 to 2.5 million yards per month, and it still wasn’t enough. In the beginning, the factory was only doing mattresses, military camouflage dress printing, and normal cotton prints. After gaining more and more experience in the field, I wanted to innovate. Those days, if you developed something new, you can make big margins from it for at least a year. After that, other factories would start to follow the trend and the prices would drop. So, I never stopped the R&D – we were the leading factory in starting Burn Out prints, Sear Sucker Prints, Glitter Prints, Spun Rayon Prints, Fujiette, and crinkle fabric.

Our spun rayon print was so popular that the total export order to the US was about 2 million yards per month at the time. The American import/export department was shaken by this number. They underestimated Thailand, as it was considered an underdeveloped country at the time. But when they saw the spun rayon from us was of great quality, and we were among the first to start printing it, they were shocked. They declared a quota limit on Thailand – we could only export to them around 22 million yards per year.

The Thai commerce ministry tried to distribute the quota as per performance, but since other factories could not produce the quality, Thonburi Textiles swept almost the whole quota, 22 million yards alone. And the profit was – I can’t even mention! [Laughs] And this was only for export, I’m not even counting what we were doing for the local market. And it wasn’t just us – every factory enjoyed this peak of the printing and dyeing industry in Thailand.

As for the lows, this industry is labour intensive. It depends on cheap labour costs, raw material costs, electric costs and lastly, the protection from imports by high import duties on textiles. When the government declared a sudden and high increase in minimum wage; and signed a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with neighbouring countries, wherein they abolished subsidies for the local industry and cut import duties on textiles; we lost ground. We were not as competitive as compared to countries like India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and China, where labour is cheap, and raw materials (such as chemicals and dyes) are cheaper, because they produce them in their country. This, coupled with the industry subsidies that those countries are receiving from their governments, means that we became less competitive. Their products are much cheaper than the ones made here, and that was the beginning of the decline of the industry, and the main cause for our fall.

What was it like to be at the vanguard of your industry, and what challenges did you face, helping to grow the industry from the ground up?

When I started my career as an Assistant Printing Manager in 1972, it was the case (and I believe it is so even now) that most of the personnel working in the field have no direct background or education in chemistry and textile technology. So, any new commoner in the factory would be directly or indirectly obstructed from going into any section to learn because the workers are afraid of someone taking their place. Not only that, but I’d received death threats as well, telling me not to come to the factory. This was the biggest challenge.

I almost quit the job after the first six months, even going so far as to submit my registration. But the owner changed my mind – at that time, I was only 22 and I’d just started my career. I’ll never forget what he told me: “Mr. Kulthorn, do you think I don’t know what’s happening to you? You’ve only been here six months and my factory was running before you came, and it will keep running after you leave. But if everyone else on the floor leaves, the factory shuts down. They’re more important. Wherever you go, if you work in a factory, you’ll run into this problem, and you will have to decide if you have the guts to survive by yourself, or if you’re going to run away.” I decided to learn everything myself and the next day, I went in and asked for books from the suppliers, and I read up on everything to do with the industry, and I discovered my passion for business innovations and overcoming challenges. Eventually, an opportunity came when I was promoted to Factory Manager after the management saw my enthusiasm, and I brought changes and developments to the factory.

What motivates you to keep working, even after decades in the business?

Since I started working in 1972, I have never had a single break for rest. I planned to retire at the age of 60, but factories call me as soon as they learn that I am free. Frankly speaking, today printing and processing is in my blood. Even beyond the duty I had to go to the factories, I would work 12-16 hours a day to get the work done. I remember my first wedding anniversary, I told my wife I’d be home by 6pm, but I ended coming home at midnight because of work. Instead of dinner and a movie, we celebrated at the kitchen table with some rice and khai jiew that I cooked, and a single candle. That was how dedicated I was, and am, to the industry.

I love to go to factories and help them find solutions to problems, chemically, through machinery, or even technology. I tell them, “dig for gold in your own factory, that is, increase efficiency and look for ways to reduce the cost of production. For example, I recently saved a factory THB 3 million per month with changes that I suggested.

To compete with outside markets, we have to reduce our prices. How? By changing the chemical processes of the dyes you use, ensuring that it’s a shorter process that is still high-quality and safe; recycling waste and waste water; setting up technology such as solar cells; reducing manpower and giving your essential workers more incentives; and by increasing production through innovative means such as modifying machinery. For example, an owner of a factory needed to print a type of fabric, but to do so, he had to buy a colour-fixing machine worth THB 12 million, which he couldn’t afford. They brought me in as a consultant, and I went back to V.P.C.’s laboratory and tried 20-30 different recipes, and I finally found one that didn’t require the machine. The owner was shocked, and even I was shocked – this was a new discovery that I hadn’t made in the last 52 years. I love the feeling of discovering solutions to challenges – they keep me going, and my mind sharp.

What would you consider some of the most notable achievements in your lauded career?

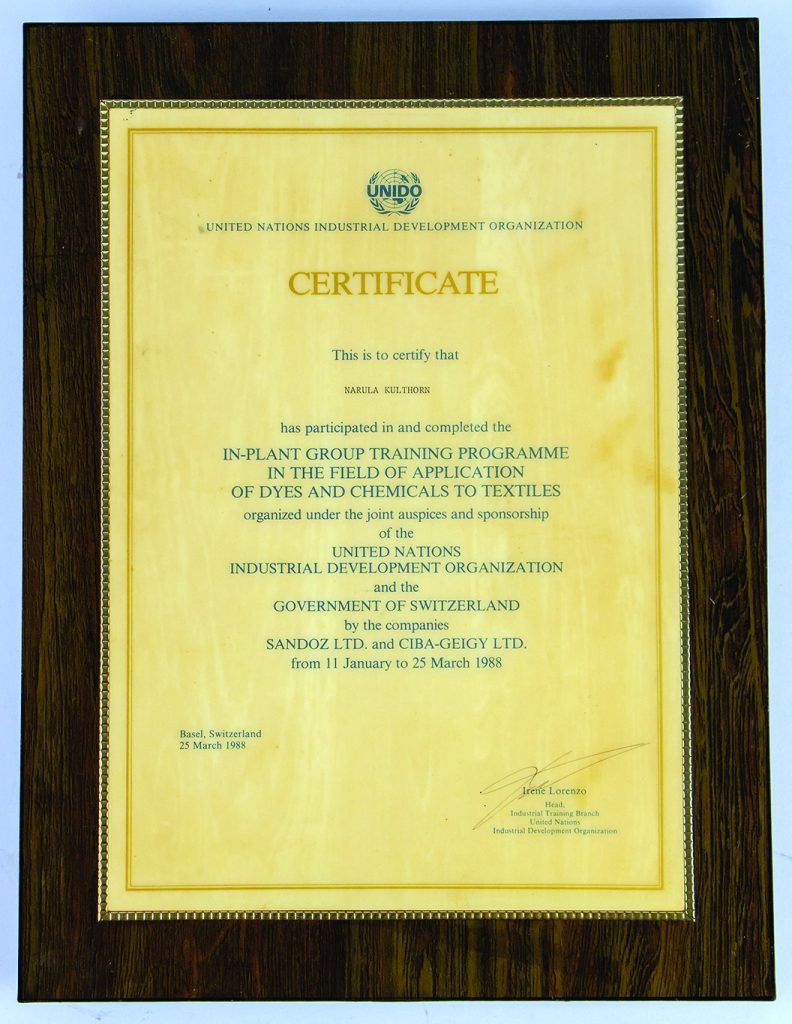

To this day, I’m still grateful that I was selected by the United Nations Industrial Development (UNIDO), a joint initiative with the Swiss government, as one of two people from Thailand to go to Switzerland for high-level technical training. This was out of a pool of hundreds of people. After returning, I became one of the most in-demand factory managers in the industry because of all the knowledge I’d received.

I also received the Hind Ratan reward from the Indian government for achievement and contributions of training Thai textile industry personnel, which I’m very humbled to have received. Other achievements I hold dear were being invited by Thaper Group to India to give them the technology to produce a special fabric which they could not produce, and to a textile factory in Pakistan to teach them the technology to produce high-class spun rayon printed fabric.

Throughout your career, how have international trade dynamics and global market trends influenced the Thai textiles industry, and how did businesses adapt to these changes? Could you highlight any specific innovations or breakthroughs you’ve witnessed in the textile manufacturing processes during your tenure in the industry?

At one point, the industry was all about normal prints (easy designs). Everyone wanted cheap products. Now, people are coming back towards slow fashion and better-quality products. Before, the cost of making better-quality designs was high, as you had to make printing plates or screens, and there were minimum order quantities to stay profitable. Since the last 8 to 10 years, there has been a new printing system called the Digital Printing System. It’s a very small machine, which only requires 1-2 employees. Short runs like 10 yards or 50 yards are possible (in the past the minimum was 5,000 yards), no sereen is required, and no colour kitchen is required.

One disadvantage which people don’t discuss, however, is that digital printing is what we call 3D printing, with depth. However, because it is only a surface printing, the fabrics will lose the prints faster, with fewer washes than conventional prints, where the dyes are thrust into the core of the yarn. And because you don’t mix the colours yourself, the price of the colours is quite high. Digital printing started in Europe and Japan and it used to be quite expensive, but then China and India started producing the machines, and now the Digital Printing prices have dropped from around THB 160 to THB 30 per yard. This has, and will continue to, change the industry. Factories who want to survive will have to adopt digital printing on top of conventional printing.

Why do you think that the textile industry in Thailand is now past its golden age, and what do you think the industry has to do to survive?

Previously, the market was ruled by our Indian ancestors, but after the Chinese produced fabrics and entered the industry, most of the Indian textile merchants have shut down their shops as they know the margin is very small, and they cannot compete. What’s happening now is survival of the fittest. The factories which are still running are the big factories, and they have good financial strength, so they’re able to keep up.

However, in this industry, if you want to survive and be competitive against China and India, you have to adapt, and implement these measures:

- Use limited workers. Advances in automation have made it easier to reduce the number of workers and machines, and give the remaining workers extra benefits. In my 52 years in the industry, I learned that worker handling is one of the most important factors to success – if the workers aren’t happy and you don’t do them justice, you won’t achieve your potential.

- Most of the technicians in the factory are used to fix supplies to avoid risks in production. Open the door for other suppliers to present their chemicals, and you can find the same colours at a cheaper cost. However, you do have to test their quality in the lab.

- Increase efficiency in production, thereby reducing the cost automatically.

- A lot of energy is lost or thrown away in the textile industry, like condensate and heat from the boiler chimney. These can be collected and used to save a lot of energy costs, which is one of the high costs in the industry.

- Install solar panels and use solar energy, which the government is subsidising, and which you can pay in instalments. It will pay for itself several times over.

- The production should have a fast turn over. These days, we can’t deliver in 2-3 months like before. It’s possible to make deliveries in 7-10 days after seeing the orders, and this will promote more orders coming in, and this way you can keep up with fabric trends.

What message would you like to convey to today’s Thai Indian community still in the industry?

Factories are still viable. It is not necessary that the factory you are running will shut down, but you have to fight for your survival. You have to adapt yourself as per the conditions. Sure, the government has lifted tax barriers, we don’t have subsidies anymore, and labour is expensive. But there are ways to survive, you just have to open those doors. It’s time for the owners or their successors to get involved in the day-to-day business, and bring in changes. Don’t just rely on technicians – call suppliers and get cheaper (but still high-quality) chemicals, reduce costs, and increase efficiency. If you do this you will not only survive, but also thrive.