His decades-long journey to becoming a pillar of the community.

By Aiden Jewelle Gonzales

Growing up as a third-culture kid, having a community to call mine was simultaneously incredibly easy and nigh-impossible. Of course, other expats, international school kids; people whose identity was not completely tied to a single culture or nation, understood me implicitly. At the same time, it was difficult for me to completely identify with the country that I’d always called home, while still clinging to elements of my roots that I held dear.

It was therefore a pleasure to meet Chuan ‘Papnii’ Thakur, newly-elected president of the Indian Association of Thailand (IAT), luminary in the Thai-Sindhi and business communities, and a father to two third-culture daughters himself, who understands this struggle and has dedicated his life to creating safe spaces for the youth and other community members to relate back to their culture. “When society becomes too big, people don’t meet each other,” he says ruefully. “Young people, when they go to school or

college, will rarely meet people from within their own community. What this means is that once they pass out from college, they get lonely. They may then want to settle abroad, and this often leaves their parents miserable. This creates a gap which I’ve been trying to fill.”

Having moved to Thailand from Pune in 1975 as a 16-year-old fresh graduate to join his elder brother, who had just started his own tailor shop, Papnii recalls how fragmented the Sindhi community was back then: “Most of the community members saw each other as competitors, so they hardly spoke to each other. When I saw that we weren’t even talking to our neighbours beyond hello, it really bothered me. I told my brother that I didn’t like that atmosphere – all we seemed to do as a community was eat, work, and sleep.” Papnii sought to change this by drawing on his childhood interest in organising cultural programmes and creating a place for people to meet each other, and suggested to his brother that they do something for Diwali as a community. “My brother discussed this with a few friends, and that is how the Diwali Ball came along, a now-annual event since 1976.”

Cultural programmes, Papnii emphasises, are at the heart of his mission to bring the community together and keep the youth in touch with their roots, programmes which he’s pushed over the years as a member of the IAT board and former president of the Thai-Sindhi Association (TSA). “They help young people meet others from the community so that they have Sindhi or Indian friends who have their back, and tie them back to the community,” he tells me. “It’s so important because, for example, schools here don’t teach Hinduism or Indian culture. When children grow in an environment like that, they often find themselves distanced from their community, and may be uneasy or lost when they come back.”

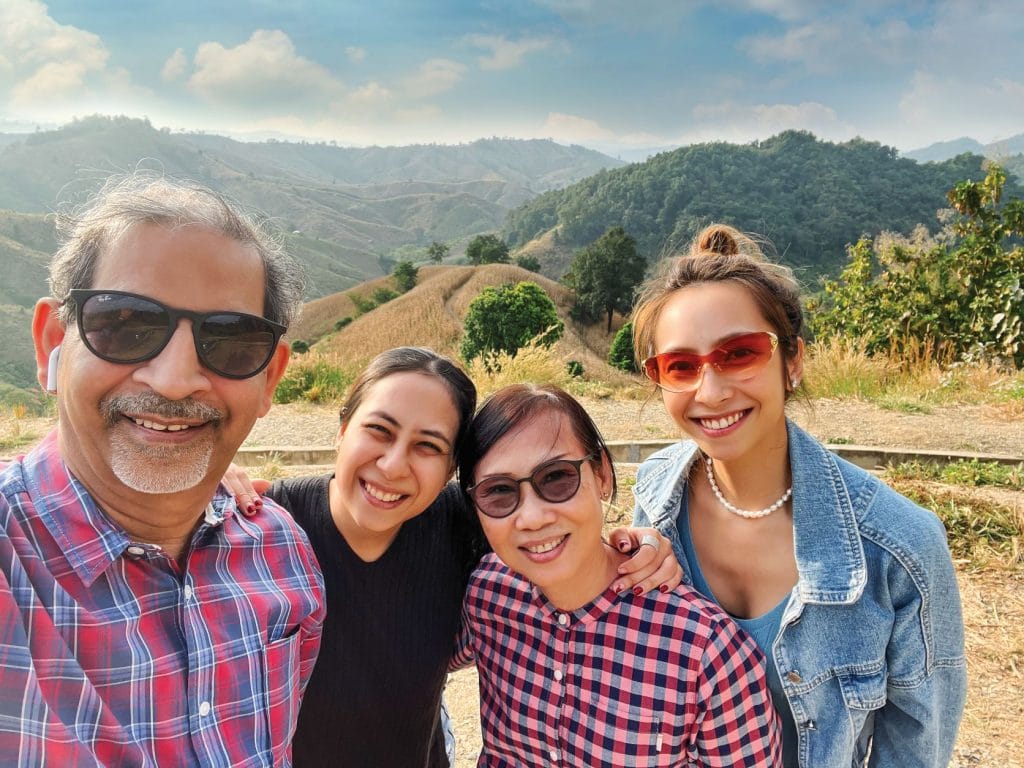

He cites his own family’s background as an example: “I live in Thailand, yet no matter how often I eat Thai food, or how fluently I speak the language, I’m still Indian. My wife on the other hand is Thai, but marrying me, a non-Thai person, has set her apart from her own community a little. Then my daughters are both Thai and Indian. While they both live in Thailand, I want to create spaces where they can celebrate their Indian heritage. I think this is the right approach, that they know about both ways and choose the one that they like. There’s no point in forcing anything on them.”

More than just someone invested in fostering the Indian community here, however, Papnii is also a savvy businessman who’s worn many hats over the years, and dipped his fingers in many proverbial pies. From tailoring, to exports, to real estate, and even video production, he’s brought his keen business acumen to industries across the board, growing his family’s business from a handful of tailoring stores to one that encompasses multiple companies and investments. What ties them all together, however, is not an appetite for risk, as I’d initially posited, but passion: “The most important consideration for me is that I should enjoy doing it,” he reveals. “I don’t do anything out of compulsion. Convert your passion into business. And once

you step in, you’ve got to give 100 percent – even more, in fact.”

He speaks to Masala further about his enthusiasm for both business and serving the community and how he’s grown his business and influence over the years.

You’re a first-generation Thai-Sindhi. Can you tell us a little more about how you’ve established yourself here and grown your business since day one, including your trials and tribulations?

It started with us four brothers: two elder than me, and one younger. The first two moved to Thailand, then I did, followed by our youngest brother who migrated here in the 1980s. My eldest brother, who himself had never been to college, had opened multiple tailoring shops here. He needed hands to help him manage these stores, and soon, the tailoring business grew quickly with all of us working together on it.

Next, an opportunity to expand to exports showed up. We jumped into exporting garments, which worked fabulously as well, and we soon became one of the top exporters in Thailand. The 80s and 90s went by in building the export business. My brothers and I worked under different banners – Jivan Products Co. Ltd, Monet’s International Co. Ltd, Niki’s International Co. Ltd – but they all led to the same pocket.

By the early 90s, we had saturated all we could do in this business, and the itch to do something different set in. You name the industry, we tried our hands in it. There was even a point where we owned two aircrafts that flew between Thailand and Cambodia. But then there was a crisis in Cambodia, and we had to sell the aircrafts off. We also had a video production studio, where we made a movie called Pra Aphaimanee, which we eventually sold off to a Thai TV channel for peanuts. I really enjoyed making movies; I still miss it.

However, what I’ve realised over the years is that not all businesses are good businesses. The grass is always greener on the other side. You sometimes jump into a business since it looks lucrative on the outside, but that’s not always the case.

Finally, we switched to real estate. The first building was easy to build, so we kept following with more. The fifth, sixth, seventh also happened equally easily, and all of it was going well until 1997. That’s when the

recession hit Thailand in the form of the Tum Yum Kung Financial Crisis. That affected us a lot, and instead of flying up, things started spiralling down.

We had taken off-shore loans, and Baht to US dollar exchange rate had gone up to 58 – it was 30 when we took the loans. This meant that the loan amount almost doubled, and we had to sell off assets in order to be able to clear it. While we eventually stepped out of the debt, this caused us brothers to separate, business wise. Unfortunately, no sooner did we separate, but each of my brothers passed away one by one. In a span of four years, it was just me, by myself. This is one of the turning points that led me to dedicate my time to community service. Now the children of the family, and their kids, have taken over the business; life goes on.

Now that the next generation has taken over the family businesses, what industries are they involved in, and what changes have they made over the years?

At the moment we have six hotels, three in Bangkok (THEE Bangkok Hotel; THA City Loft Hotel, and The District Hotel), two in Chiang Mai (THEE Vijit Lanna by TH District, and THEE Chang Thai), and one in Hua Hin (THALAY Cha-am by THA). THA is from our last name, and we use ‘thee’ a lot, which means you or God in Old English. They’re all managed by kids of the family, all of whom came to me with their thoughts and new ideas after my brothers passed away. I keep encouraging them to execute things the way they want. All our

hotels are therefore unique in their own way, because they all have different ideas. What is the same though, is the service, which is the most important thing in the hospitality industry. You need to serve your clients well so that they keep coming back to you.

It’s admirable that you allow them to be their own entrepreneurs, and don’t micromanage them. All too often, there’s an expectation for kids to join the family business and run it in a certain way.

Our children today are very well-educated, unlike us who just passed out of school and went straight into business. We rose because we were street smart. Now, the children have the education to back them up, and they know what they’re doing. They’re investing in technology, listing us on online platforms such as Agoda,

which has immensely diversified business; they’re investing in the stock market and in cryptocurrency; they’re self-sufficient, and I encourage them in that.

If they don’t want to join the family business, that’s fine too. I have two daughters, Ratika Thakur, who works for Christian Louboutin, who’s deeply passionate about fashion and shoes, and who heads the Thailand section of her department; and Minnie Thakur, who just graduated from INSEAD in Paris, and now works for Siam Commercial Bank. Both my kids didn’t want to continue doing what I was doing, and that’s ok. I’m deeply proud of what they’ve accomplished, and of my wife, Reena Thakur, who’s had the hardest job of all – taking care of all of us over the years.

Now, I’m happy to leave everything to the younger generation. I’m no longer after business – I never close doors of course, but that’s not what I am after. As I’ve grown older, I’ve realised if you have too much going on, you won’t be able to find happiness. For me, community service brings me that happiness. When I help people, I feel fulfilled.

Now that you’re dedicating your time and efforts to the community, tell us a little about that.

In Pune, we made a Sindhi Jhulelal temple (Vimla-Jivan Jhulelal Hindu Mandir – Pune) for the community. It was my mother’s wish, and my elder brothers wanted to build it as well. I am a part of the board of trustees for the temple and we have built it under the Thakur Foundation. Now it’s a landmark for the Sindhis of Pune.

Here in Bangkok, I am a part of the Lions Clubs International chapter in Thailand, and I’ve been its president twice, I was the President of the TSA, and I’ve served two terms as the Executive Director of the India-Thai Chamber of Commerce (ITCC), and in all these capacities, my aim has been to work for the community without any biases against who the person on the other end is.

I tend to have a good rapport with people in general, and so whenever I ask them for a favour, they rarely deny it. And then, once they help out, I’m always appreciative. I ensure that they have recognition for what they’ve done – and I pass that gift forward. My motto is to help unconditionally whenever I can, and even if I personally cannot help them, I direct them towards where they can find help.

A big part of this was spearheading a lot of cultural programmes, first for the Sindhi community, and then it widened to the Indian community overall, once I joined the Lions Club. No matter what we say, our heritage is mixed; we are Indians in Thailand. And that is where a society like the IAT comes into the picture. Over the years, we’ve organised the now-annual Indian-Thai Sports Day, because with sports, there is no divide – it brings together Indians of all communities, from Sardars, to Gujuratis, Punjabis, South Indians, and more.

My main focus has always been to unite people. My emphasis is often on activities for youngsters, because if I conduct a cultural program for children, their parents would definitely come too, and bring the rest of the family. Then all these families can meet each other and that is how you build connections.

You’ve mentioned the importance of the IAT, and you’ve just been elected as their president. In this capacity, what are your goals and objectives to further serve the community?

The plan is to continue with the sports day, and with community service. For example, we as the IAT team created the Youth Forum and the Ladies Forum, both initiatives that I plan to grow. The former encourages events for children, such as the fund raiser we did during the pandemic when we sold cakes baked by children, with the proceeds going to charity; and in the latter, housewives come together to create small handicrafts, embroideries, or paintings which we then put together in the form of an exhibition, in order to give their small businesses more exposure.

At the end of the day, it’s a team effort – it’s impossible for one person to do all this, but one person can have 10 different ideas, and your team can execute it.

From growing your business from scratch, weathering several crises including the recent pandemic, bringing to Thailand and mentoring many aspiring businessmen, and executing an array of important community initiatives, you’ve been successful by any definition. What do you attribute your success to?

Firstly, be honest and sincere with your clients. We don’t have any tricky business, you have to be an open book. Don’t be afraid to be spontaneous in order to fulfil customer requirements and perceive what they need. We never took advantage of anybody, even if that means that we have less. At one point we had everything, and then everything slipped away. Life is like a roller coaster: money comes, money goes, what’s important is happiness. Secondly, you’ve got to have passion: for business, for the community.

What is the main difference between the Sindhi community when you arrived here in Thailand, and the community now, and what things have stayed the same over the years?

One thing that has been consistent over the years is that we Sindhis are hard workers, and inherent entrepreneurs. You must be careful before you hire a Sindhi because they might take your business away!

[Laughs] When we migrated from Sindh in Pakistan to India during the partition, it was quite a difficult time, and we had to start from literally zero, but we’ve learned to work hard. We’ve also always been, and still are, great mixers. We blend in with communities easily, no matter where they go: in Spain, we are Spanish; in Thailand, we’re Thai. We respect the country and culture we are in and yet hold our own culture intact.

What’s changing is that people are more open to, for example, allowing their sons and daughters to marry outside the Sindhi community, and even people who aren’t Indian. We’ve become a lot more open over the years. However, a negative is that we used to be more connected. Now, entertainment has swept over everything, and due to everyone being too busy online, people don’t want to attend cultural programs.

That’s why this is something that I’m continuing to push in different ways, so that we can go back to being more connected to each other.

Finally, as an influential member of the Thai Indian community, what message would you like to give to the community?

Don’t ignore your fellow citizens around you. If there is anyone in the community that needs help, and we don’t help them, that person will start sinking. Even if you can’t help them, at least direct them to

Papnii! [Smiles] We may not be able to help 100 percent of the time, but we’ve got to do what we have to.