As the Founder of Sati App, he shares his inspirational work.

By the Editorial Team

Content warning: suicide and self-harm

My concerns with my mental health began when I was only 17, and they’ve evolved into complex issues I tackle in my day-to-day life. What has remained constant, however, is that I continue to find it difficult to talk about my struggle with anxiety because of the judgment that comes with people thinking you’re ‘troubled’ or ‘different’. I’m sure there are many others in the community who feel the same way, and so I’ve always believed that there is much more we can do as Thai-Indians to dismantle the stigma associated with mental health so that less people have to suffer in silence.

Someone who shares this belief in making the world a kinder, more inclusive place is Amornthep Sachamuneewongse. A graduate from Mahidol University International College, Amornthep obtained a degree in marketing and was employed in the airline industry before moving to work with his family in hotels. It was during this transition that he began developing depression and schizophrenia. Now studying a Master’s in Psychology and Neuroscience of Mental Health at King’s College London, Amornthep is committed to mitigating Thailand’s growing mental health crisis through founding Sati App (www.satiapp.co), an on-demand listening platform that connects individuals with active listeners to aid with crisis prevention. He shares his journey with Masala.

What was your impetus behind joining the mental health advocacy space?

In 2016, I started seeing a psychiatrist and I was diagnosed with major depressive disorder and schizophrenia. Considering it was nine months after I had fi rst began experiencing symptoms, the situation had gotten pretty bad, I was experiencing hallucinations, was self-isolating and self-harming. By April of that year I had to take 16 medications per day. I went through electroconvulsive therapy, which uses electric shocks to charge the neurons in your brain, about 30 times but soon had to stop because the medication caused my weight to go up from 95kg to 147kg and I began to stop breathing under anaesthesia.

I was then in and out of hospitals and nobody could understand what was happening to me, whether the hallucinations or why I couldn’t smile or feel anything. As a result, every time someone couldn’t understand me I would blame myself and that would set me back through this loop where I would harm myself and go straight back into the hospital.

In 2017, I attempted my first suicide. When I left the hospital, I was blamed for my actions because people couldn’t understand why I did what I did, when really I did it because I felt like I was a burden to everyone and that I couldn’t be helped. In 2018, I began posting violent messages on Facebook to the point where Facebook actually sent me a notification asking me if I was okay and if I needed to talk to someone.

Later that year, I attempted my second suicide. This time, I called a hotline before I did it but nobody picked up my call. When I was discharged from the hospital, I was really angry that no one picked up when I needed it, so I began doing more research into the mental health problems in Thailand to fi gure out what I can do to solve them. That’s how the idea of the application came up.

In 2016, I used to drive for Uber because it made me happy, and so I thought if they can make it so easy that

you click a button and a car can pick you up and drop you off, why can’t I do the same for people who need someone to listen to them? So that’s where I drew the idea. I began developing the app back in 2018 and just launched it in April of this year. It’s been very overwhelming but exciting at the same time.

There are a plethora of apps targeted at mental health support. Did you draw any inspiration from them or did you develop Sati based on needs unique to your experiences?

When I had yet to figure out my diagnosis, I tried apps like BetterHelp, Headspace and 7 Cups but found that what was really missing was that person on the other side. I scanned the internet trying to fi nd if there was anything that provided this service for free, but I couldn’t find anything. That’s when I decided that in this whole country, there must be at least 100 people who would volunteer to listen to someone who needs it. It must be possible to make this app a reality.

In 2018, I was invited to an event where unbeknownst to me, I was sat next to the President of the National Suicide Prevention Centre (NSPC). During the event I was bashing the Department of Mental Health (DOMH) and at one point he turned to me and said ‘we need to talk afterwards’. He ended up inviting me to present the work that I wanted to do at the DOMH and that’s how I secured their support.

Launching a digital platform is by no means an easy feat, what kind of process did you go through?

I’m not from a tech background so I was naïve to think it would be easy! Once I had the design finalised with help from a friend, I asked several app developers to quote me a price.

Of course, everywhere I went quoted me double the amount that the DOMH was willing to support me with, with prices going up to THB 1 million. So my first problem was: how can I find a cheaper alternative?

I’m a part of the Global Shapers Community, a tight-knit network of youths who are trying to solve the world’s most pressing issues. We have tens of thousands of people around the world from various backgrounds so I decided to post on the community page asking for app developers to collaborate with me. This is how I met one of my co-founders.

Ondřej Nádvorník is a Shaper from Praha, Czech Republic and his involvement in the mental health space began when his cousin committed suicide. Now our CTO, he told me that he would give me a 50 percent discount on developing the app and we’ve been working on it together ever since. He’s part of the reason we got a letter of intent signed by the National Institute of Mental Health in Czech Republic stating that they will launch Sati in the country. We are also establishing Sati App Foundation in Europe and launching the app in other places as well.

When planning, I really lacked organisation skills because I was too busy dreaming about the future [laughs]. For me it was so important to advocate that I forgot the importance of the organisational side and that’s where our other co-founder Chanon Wongsatayanont came in. Our COO, he’s got great organisational skills because he runs several hotels, but he also has a degree in Psychology from Oxford University so he’s been of great help with planning how to move things forward.

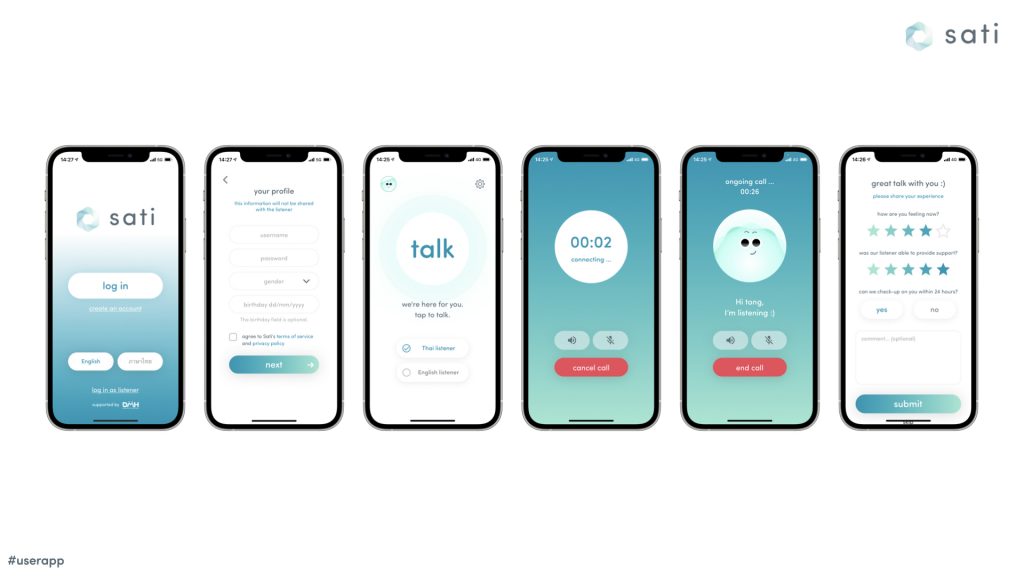

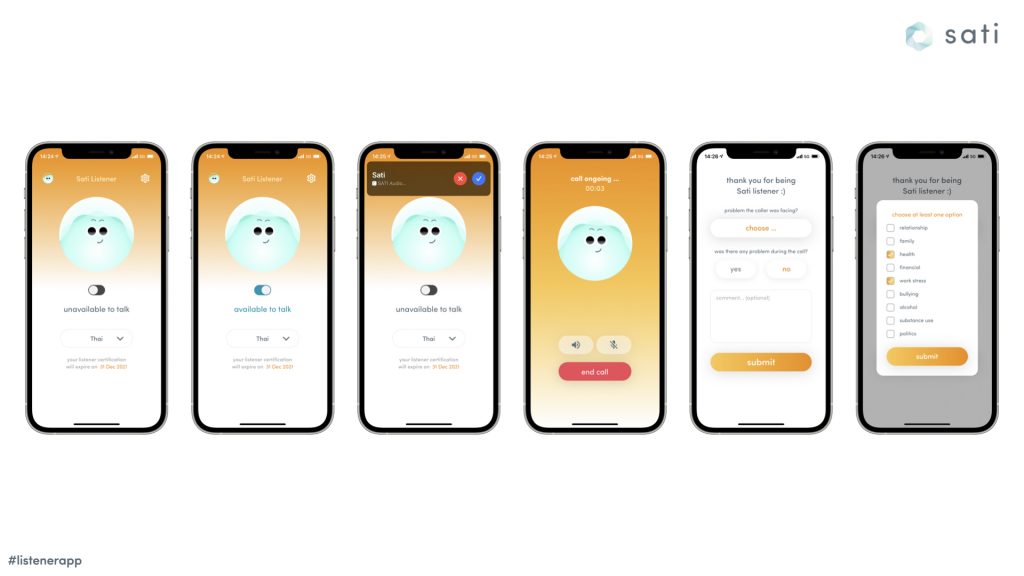

So how does Sati App work exactly?

I used to have a lot of panic attacks and I had this friend I would call who would always tell me to “thang sati,” which roughly translates to ‘staying in the present’. That’s how the name came to mind. During initial research, I looked into the affordability and accessibility of mental health care in Thailand and the range of prices was staggering. It illustrated that if you were not from an affluent background, it would be difficult to get proper care.

When we developed the app we used the WHO Pyramid Framework that had peer and community support as its base. This was inspired by Dr. Dixon Chibanda’s work in Zimbabwe where he created this idea of the ‘Friendship Bench’ to connect trained grandmothers with teens who needed guidance. Through this, he was able to reduce the suicide rate in these communities by 20 percent. This parallels Sati’s goals as we want to build that peer support network, too.

In 2018, Thailand’s 1323 Call Centre had over 800,000 calls. Only 20 percent were answered because there were such a limited number of volunteers. However, because it’s a fixed landline system, it’s very hard to increase the number of landlines. We became aware of all of this and developed Sati to be able to act as another channel, and as a means of collecting important information about stress factors in different demographics in the country. To date we have over 3,358 users and 129 listeners but we have 1,200 more to be trained next month. So this is just phase one that we’re working on.

Struggling with one’s mental health is still considered a stigma in the Indian community, what are your thoughts on this?

It’s a hard thing to tackle because we’ve never had mental health in our equations of success or well-being. We still believe that if men cry then they’re weak, if you can’t handle stress then you’re a failure, when it goes far beyond that and we need to understand mental health better to be able to address the stigma.

When we look at mental health, we can use a Venn diagram with three circles: biological, so genetics, neurochemistry, and gender; psychological, so past traumas, abuse, sexual violence, unhealthy coping skills; and societal and cultural factors. We need to honestly ask ourselves, is the Indian community actually opening up? Do we have a peer support network in the community? If these things are not in place then people can go to psychologists and psychiatrists and still not get better because we all need proper peer support.

One thing that puts a lot of stigma on mental health is social status. We often hear families saying: ‘what are others going to think?’ When that comes into play, it puts a lot of pressure on someone who might not be well. They’ll think: ‘If I open up, my family might not be happy with me because I have tarnished my family’s name’. We’re such a tight-knit community that we need to overcome this kind of thinking. We’re too focused on sweeping everything under the rug that we’re not ready to accept each other yet.

How many Indians right now are openly depressed? How many are openly addicted to drugs or alcohol? How many have experienced domestic violence? We have all of this in our community and it all links to mental health but we’re not ready to accept it because we’re worried about what society might think of us. This needs to change before we can really start having conversations about mental health.

How can we facilitate important conversations about mental health in our smaller circles?

It can be an extremely difficult thing to do because it’s so personal. If you don’t know where to start, start by writing everything down. Once it’s written out, you can reflect and have a clearer picture of how you want to proceed. Also, have an ally, which is one person you can go to for anything.

If you’re old enough, I recommend going to see a doctor. Do not Google your symptoms because symptoms can overlap and you can easily give yourself a wrong diagnosis. For me, I love going to see my doctor because it’s the one hour that I have where someone is actually listening, and is reflecting on my pain, my suffering, and everything.

I’ll be frank in saying that if you think you are not okay, please go see a psychologist or psychiatrist and get your diagnosis first before seeking alternative therapies from a life coach or through reiki.

How can we connect our loved ones to the right resources should they need them?

Focus on the three Ls: look, listen and link.

Notice if their behaviour has changed or if they’re partaking in riskier behaviours. Once you’ve looked for the signs approach them and say: ‘hey I’ve noticed you’re not acting the same, is there anything going on? If there is, know that I am here for you and I am ready to listen to you and support you.’

When they speak, rather than trying to fix their problem say: ‘thank you so much for sharing, it must be so hard with all that you’re going through right now. You said you are stressed about X right now, can you tell me more about it?’ Pick up points you think they are stressed about and ask them to elaborate more.

The more you’re able to ask them open-ended questions, the more it allows them to express themselves and reflect. If after 14 days you feel like the person is not better, it’s important to link them up with a doctor as they may have some kind of mental condition that requires professional assistance.

Thailand’s mental health crisis is growing as a result of the pandemic, how has this affected the work you are doing?

Post-COVID there’s going to be higher rates of anxiety and depression so we need to be prepared for that. We’ve already seen higher numbers of suicide last year compared to the last 18 years, 1,586 and that’s underreported numbers. Major factors were relationships and finances, which demonstrates that mental health is not just about health, it’s about relationships, the economy, drug and alcohol abuse, so many things.

We’re also working with the NSPC and the DOMH to train volunteers in vulnerable communities in basic psychological first aid. We’re trying to be offline as much as online as there are people who do not have access to the internet, elders who are lonely, and so on. Last year we trained about 250 volunteers and we are planning to continue this work in December.

We’re also coming up with strategies on how the media should report on suicides as we’ve found that if media continue to provide news without any censorship, this leads to what we recognise as copycat suicide. Thai news also don’t cite helplines when reporting, it’s often just about the drama, so we need to change this. We’re also looking to launch our own tele-psychotherapy platform so that if someone calls, we can connect them directly to a doctor after the call. We’re working on a lot at the moment!

What can we do to support Sati?

You can help fund our work via SocialGiver or donate to us directly and get a tax receipt. You can also volunteer with us once we’re recruiting listeners again. Definitely get yourself trained in basic psychological first aid via our e-learning programme that will allow you to become a certified listener, as the more people who can offer support on a community level the better. Finally, learn what it means to truly listen from your heart and to support someone you might not wholly understand without judgment. Whether it’s friends, family, or a stranger.