He’s reaching for the extraordinary in all he does.

By Aiden Jewelle Gonzales

I’ve always considered the term ‘civil service’ to be a beautifully apt moniker – at its core, it’s serving all citizens, regardless of age, gender, status, orientation, or any other qualifier. In a broader sense, it’s contributing to the welfare of not just the citizens of one country, but to global citizens; all of humanity. As someone who studied politics back in university and was thus fed a steady diet of political philosophy, my natural cynicism of the world around me is tempered by an optimistic view of the role that government can and should play in our lives, especially in changing the public sector for the better. Thus, when I met Ravi Sawhney, who’s been in civil service for decades, and to boot, has recently published a much-lauded book – a long-time aspiration of mine – I’ll admit that I was a little in awe.

“I’ve had a very eventful and fulfilling life, and a career spanning about 40 years in the national and international civil service,” Ravi concedes with what I soon discover is his characteristic charm. Although he admits that he had “a somewhat reluctant start in government service,” he nevertheless tells me, “I consider myself fortunate to have gone through a career that offered immense opportunities to do something fulfilling and lead a meaningful life. And at every stage, I felt inspired to do the extraordinary. Yes, there were challenges, but these only made the journey more exciting!” Indeed, I was impressed to learn that not only had Ravi been part of the Indian Administrative Service (IAS) and the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP), but he had been instrumental in establishing various industries and Red Cross institutions at the national level, as well as the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC) and NIST International School, at the international level.

Included in his rich and storied achievements was his involvement in a back-channel effort to “bring rapprochement between the Akali Party and the Congress parties which, had it succeeded, might have averted Operation Blue Star and its aftermath,” – a fact that shook me with possibilities of what could have been.

Born in Abbotad, a cantonment town in the Northwest Frontier Province of India (now in Pakistan), Ravi walked me through his early education, which culminated in qualifying for the LL.B degree from the Faculty of Law, Delhi University. “In those early years of India’s independence, the emphasis was essentially on getting quality education without any thought of career planning. Not being a business family, my father was keen that I acquire a professional degree and hence the degree in law,” he explains. “The education I received in the school and university prepared me to pursue initially a career in the legal profession and thereafter in government service.”

He spoke to Masala further about his journey of service that, I can say with conviction, went beyond the mundane and touched the exceptional.

What drove you to join the IAS, and what did your posting there entail? How did your experiences change your paradigm and how you approached the world?

Strange as it may sound, I was a reluctant entrant to the IAS! I was aspiring to join the foreign service (IFS), but in that year (1968), the intake quota for the IFS was inexplicably low – any other year, I could have easily joined. I was therefore faced with the dilemma of joining the IAS or continuing in the legal profession. My father advised me to join the IAS as I could still retain the option of reverting to the legal profession if it wasn’t to my liking. I thought that made eminent sense, so I joined the IAS only to realise later that it’s easier to join the service than to leave it!

I worked in Punjab for the first 15 years of my career, and my postings there were mainly related to rural development, industrial development, and district administration. My first substantive posting was in Hoshiarpur, a backwards district of Punjab. After the initial short tenure as Sub-divisional Magistrate, I was put in charge in of a newly-formulated national programme to assist marginal farmers (owning less than one hectare of land) andlandless agricultural labourers. Our aim was to alleviate their poverty by providing them with supplementary sources of income.

Initially, I approached my new responsibility with considerable trepidation as it was a far cry from the diplomatic life I had envisaged, but I soon realised what a great opportunity I had been given to do something meaningful, to better the lives of the impoverished rural community. It was then that I went through a kind of metamorphosis and got enthusiastically involved not just in implementing the programme, but in looking to do something extraordinary.

Dairy farming was one of the components of the programme to supplement the target group’s source of income. I formed the target beneficiaries, marginal farmers, and agricultural labourers, into village-level, milk-producing cooperative societies. To ensure they had a market, I set up a cooperative milk plant, perhaps the first of its kind in Punjab. This was the first big industry in Hoshiarpur district, and it’s a matter of great satisfaction that the plant subsequently doubled its capacity and is now benefiting thousands of families. This experience in the first few years of my career was very fulfilling and made me realise that the service offers great opportunities to do the extraordinary and that, indeed, set the tone for the future.

Can you share with us how you’ve overcome some of the challenges associated with government service?

In Indian government service, there is great diversity in the responsibilities you are assigned, as well as the challenges. These include the seamless transition from one job to another, often working under great pressure, and at times, the public’s negative perception of the bureaucracy.

I believe much depends on one’s approach to a job. One can choose a passive approach as a safety measure, and just do the minimum required without being faulted; or take a more dynamic approach, as I did, to look for opportunities to do something extraordinary regardless of the risk factor. If one has the courage of one’s conviction, challenges are not insurmountable.

What would you consider your biggest achievements during that time, and what accolades are you most proud of? Why?

During my 15 years in Punjab, I was fortunate to be given mostly operational and challenging assignments. The establishment of a cooperative milk plant in Hoshiarpur; promotion of industrial joint ventures especially in the electronics sector in the State; conceptualisation and formulation of the first integrated rural development programme in the State; and effective maintenance of law and order as Deputy Commissioner, Ludhiana, during a very turbulent period in Punjab; gave me a great sense of fulfilment.

The accolade I cherish the most came when I completed my tenure as Deputy Commissioner in Ludhiana. The Akali Party, which was then in the opposition and had been carrying out a relentless agitation against the Congress government, honoured me in an unprecedented gesture, with seven seropas (presentation of sword and scarf) to acknowledge and appreciate my non- partisan and effective handling of the law and order situation. Even though at times I deviated from government directives, we thereby ensured Ludhiana was the most peaceful district in the State.

To put this achievement in proper perspective, I should mention that at times Ludhiana district was at the centre of the Akali agitation and taking advantage of that, violence was perpetrated by the militants led by Bhindranwale. I therefore had to deal with some highly-explosive situations, which could have led to widespread violence not only in my district, but across Punjab. The renowned editor of a widely-circulated newspaper was assassinated while transitingthrough the district, which could have led to widespread retaliation; the Akalis called for “jail bharo” to step up their agitation, and all the leaders courted arrest and were in my custody in Ludhiana. This was also when I got involved in the efforts to avert Operation Blue Star.

Apart from the achievements in my direct line of work, there are some others worth mentioning, the primary credit for which must go to my wife, Madhu. While in Ludhiana, we set up a senior citizens’ home under the aegis of the District Red Cross Society, of which Madhu was the Chairperson. Although the concept was still considered alien, the response from across the country was overwhelming. We had foreign delegations visiting to study our model of a home run by the guests themselves.

We also provided board and schooling to the healthy children of leper parents, with the parents’ consent, in a facility adjoining the Senior Citizens’ Home, so that the children wouldn’t be condemned to live in a leper colony. The senior citizens became their ‘foster grandparents’ and a mutually happy relationship developed.

Moreover, we developed another facility in the same premises to provide vocational training to physically-challenged children. Finally, noting the shortage of blood supplies in hospitals, we not only organised regular blood donation camps, but also established a fully well-equipped blood bank that could meet the needs of the entire State.

You were instrumental in the establishment and conceptualisation of BIMSTEC. Tell us a little about that, why you pushed for this initiative, and what you consider so important about it.

During my tenure in the United Nations ESCAP, I coordinated a thematic programme, Regional Economic Cooperation, which among other things, tried to promote institutional economic linkages between the various sub-regional organisations in the Asia-Pacific region, with special emphasis on ASEAN and SAARC. However, ASEAN appeared reticent to develop institutional-level linkages with SAARC because of the latter’s internal conflicts.

At that time, India had declared a ‘Look East’ policy and Thailand a ‘Look West’ policy. I therefore proposed to the littoral states around the Bay of Bengal a new economic community to promote inter-se trade and economic cooperation, focusing on trade expansion and strengthening multimodal transport connectivity, and the response was positive.

BIMSTEC is a framework agreement which can strengthen trade and economic relations between countries of South Asia and ASEAN, and thereby more fully realise their existing potential.

You also established NIST International School. What was your vision for it at the time?

At the very initial stage of my joining United Nations ESCAP, I got involved in an initiative to establish a United Nations school in Bangkok, keeping in view the large number of UN agencies located here. Unfortunately, we received no support from UN headquarters, but as some momentum had already been built among the expatriate community in Bangkok, we decided to go ahead and establish a “truly international school” based on UN ideals.

The existing international schools were, in their curriculum and culture, either American or British schools, albeit for international children. In such schools, there is often a lack of understanding of the other cultures and countries of the other children. I realised this when my daughters, Ravina and Aushima, joined school here, and we had to move them from one school to another.

NIST meets the requirement of a “truly international school” both in its curriculum and its culture. My youngest daughter Raisa graduated from NIST, and presently my granddaughter Riana is studying there. Hopefully, my grandson Aryan too will join NIST in due course. I am still involved in the school as a Founding Member for life on the School Foundation, which is the apex governing body.

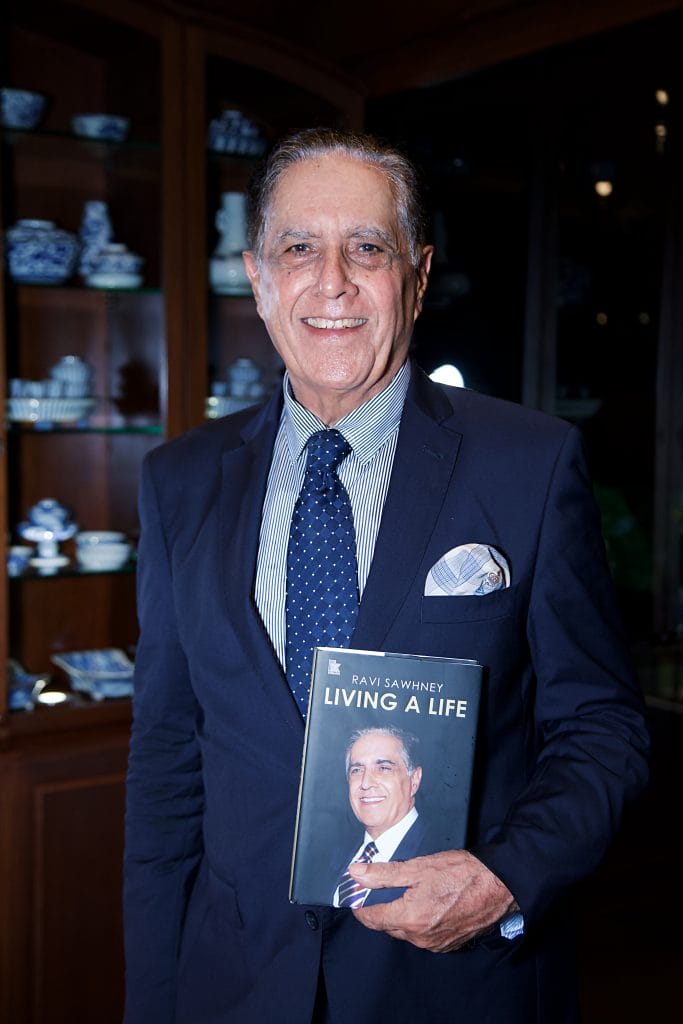

You recently wrote a memoir called Living a Life which has received many accolades and praise. What inspired you to write it, and what message did you hope to convey with it?

I was prompted by my family and peers to document my life’s experiences, which have been eventful and fulfilling. The central message is that while life is God’s gift, how you live it is entirely up to you. There are choices to be made on how you wish to deal with the opportunities and challenges thatconfront you. You can go through life either just existing, or actually living it. I believe I have lived my life seizing the opportunities and relishing the challenges. Hence the title of my book, Living A Life.

As the book reviews indicate, my book shatters the myth that in government service there is no scope for innovative thinking or to be enterprising. It has been described as an ode to the lost breed of civil servants, and thus viewed as inspirational and recommended to be read by the aspiring youth in academies and training institutions.

his home in Palestine.

You’ve met many influential figures over the years. Who would you consider some of the most inspiring people you’ve met, and why?

In a career such as mine, you do get to meet many renowned and influential figures. As Deputy Commissioner, I hosted King Charles III’s (then Prince Charles) visit to Ludhiana and interacted with Mother Teresa. While in the Commerce Ministry, there were many meetings with prominent leaders from other countries. Then in the UN, meetings with heads of government and influential leaders were frequent. As coordinator of the UN programme for the newly independent Central Asian countries (SPECA), I interacted with their Presidents to understand their aspirations under the UN programme.

However, the figures I have been most inspired by are quite different to those I interacted with in my official capacity. During my student days as an athlete, Milkha Singh was my great inspiration as I, too, ran the 400m, and I was privileged to briefly train with him. Then there was the relatively lesser-known Bhagat Puran Singh, who I met when I was undergoing training in Amritsar, Punjab. When India was partitioned, he came across the newly- established border carrying a lame man on his shoulders, leaving all his belongings behind. He then established the Pingalwara in Amritsar, a home to look after the disabled and suffering masses, including many abandoned by their own families.

Another inspiring figure also involved in ameliorating the lives of suffering humanity is Mother Teresa. I was fortunate to meet her when she visited Ludhiana to establish a branch of the Missionaries of Charity. There was opposition by political leaders based on a misconception of her mission. I allotted her a site in spite of considerable political pressure against it, and it was like a blessing when she visited my home to express her gratitude.

Here I might interject with our own experience, inspired by the above two, in turning around the life of someone who was a polio victim and went around begging on a roller slate. We gave him a kiosk under the aegis of the Red Cross to sell soft drinks in the compound of the civil courts in Ludhiana. Years later when we visited Ludhiana, we met him. He had gotten married and had two school-going children.

Among the international political leaders, the most inspiring for me was Yasser Arafat, who had fought relentlessly for the cause of the Palestinians. It was such a great privilege to meet him in his home in Jerusalem just a few months before he passed away and to hear from him in person about his life-long mission.

Tell us about your biggest support and inspiration over the years.

My biggest support and inspiration has initially been my parents, and later my family. Born before the partition of India, I was brought up during very turbulent times and when India was still struggling to keep its “tryst with destiny.” However, my parents never made my two younger brothers and me feel insecure, and in spite of all the challenges that they must have confronted, they gave us the best upbringing and education. They instilled in us proper family values and whenever I was at a crossroads, my father was there to guide me.

Later, my wife Madhu has been there both to share my successes and to support me and boost my morale whenever we faced adversity. Now, my children, too, have become a great source of support and encouragement.

What new horizons do you hope to explore in the future, both personally and professionally?

Frankly, as a retired man, I’ve no definite plans yet. I have been invited by some educational and training institutions in India to talk about my book, which I propose to do later this year. I might even get down to writing another book; more for entertainment. At the personal level, if I can lower my golf score and lose fewer golf balls in the water hazards, I’ll be happy! [Laughs]